Why ImproVeto exists

After a game of Bluebeard’s Bride (which explores feminine horror with a guaranteed unhappy ending), we ended up talking about difficulties we’ve had with using safety tools like the X-Card in our games. As players, some of us worried that taking something uncomfortable-to-us out of the game would somehow ruin the cool things the GM had prepared. As both GMs and players, some of us worried that we wouldn’t be able to spontaneously adapt our carefully prepared ideas if someone else took out an element we had just introduced, or that our ideas in doing so would be boring to our fellow players.

My game design brain immediately went to “I should make a game so people can practice that!” — so that’s what I did. Here’s how.

Design decisions that went into ImproVeto

I knew I wanted to create a stand-alone game that would offer a low-pressure environment for people to practice both x-carding an element and adapting to that spontaneously.

The basic play loop of “tell a story, get interrupted, adapt the story, then hand over the storytelling to someone else” (or, respectively, “listen to a story, interrupt it with an X-Card, listen to it being adapted, then take over and continue the story yourself”) was clear to me pretty immediately.

I also quickly arrived at the title ImproVeto that mashed together the two main components of the game: “improv” and “veto.” I briefly wondered if that wasn’t a bit too on the nose, but in the end decided that I liked how it told you exactly what you’d get.

The main task in designing ImproVeto was finding an answer to the question: How to enable players to practice using the X-Card without reproducing situations that were genuinely uncomfortable to them? After all, that was what we had gotten stuck on before!

The answer was of course: Lower the stakes, so everyone would feel safe enough to do two emotionally risky things in this game I envisioned:

- Improvise part of a story without any preparation and with limited control over where it would go.

- Veto someone else’s ideas.

A lot of design decisions went into baking this fundamental principle of “lowest stakes possible” into all aspects of ImproVeto:

- Making the game GM-less and having as little hierarchy at the table as possible, since any hierarchy might make it harder for people to trust each other with the emotional risks required by the game.

- Making the basic rules and the turn structure as simple as possible to reduce cognitive load and help players focus on the core of the game. This is why only one table with extra input made it into the final game and why its use is completely optional.

- Making the game 100% no-prep, so anyone could pick it up and facilitate it without any previous experience.

- Making the game duration as short as possible (one turn each, more optional) because I assumed players would be more willing to give a game like this a shot if it didn’t take over a whole session. This also enables players to easily integrate the game into a Session Zero, use it as an ice-breaker with a new group, or just run a quick session with a friend or two whenever they have a little time.

- Enabling players to veto a random element instead of waiting for something they genuinely don’t want in the game to minimize the stress of saying “No.”

- Providing a random roll table to create a starter scenario to make it as easy as possible to begin playing and to minimize the need for lengthy discussions before the game).

- Making the random roll table as trope-y as possible (so everyone would have some immediate associations to build on), while also throwing in one or two unexpected elements (which often generates humor) and making the possible combinations as absurd as I could (to prompt players to find explanations for why these things came together, which already is halfway towards a story). From the get-go, this nudges players towards telling a story that is light-hearted and fun, which lowers the chances of introducing uncomfortable topics or triggering anyone’s trauma for real.

- Asking players to tell a shared story (instead of many individual ones) to give everyone at least some control over how the narrative developed and to encourage an atmosphere of collaboration instead of competition.

- Adding a list with tips to help with improvisation, especially for players who are new at this or who need some extra support in breaking down what goes into advancing a narrative.

- Adding regular safety tools to the “What you need” list so players would have a way to differentiate between the game mechanic that ended up being called “Veto” and an actual X-Card in case that was needed.

- Playtesting the game multiple times with multiple people before publishing it to make sure it actually did what I wanted it to do and I didn’t promise anything I couldn’t deliver.

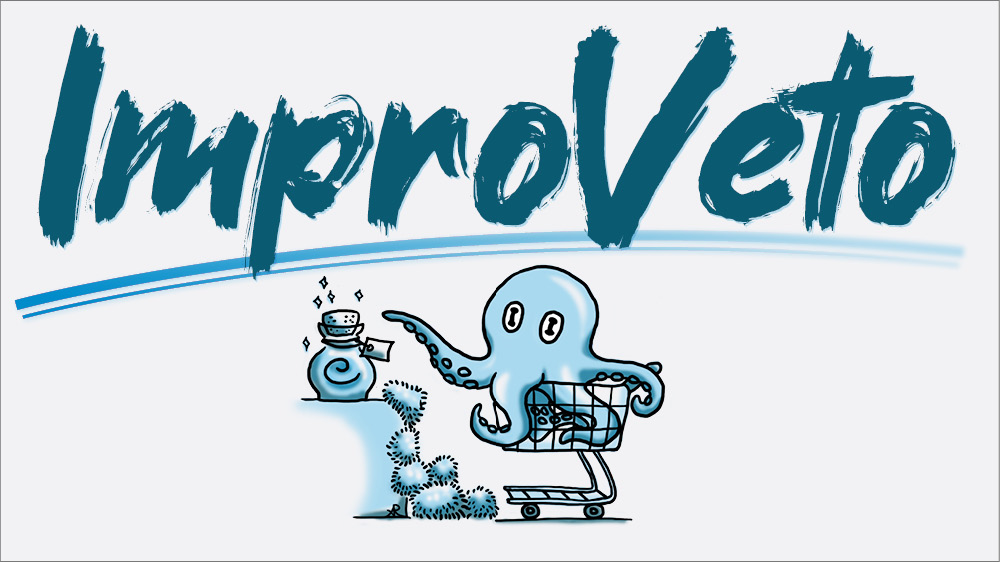

The Visual Design of ImproVeto

When it came to the visual design, I wanted it to support the game’s whole vibe. I first picked a brush-script font for the headlines to underline the handmade, improvised aspect of the game.

Then I chose Atkinson Hyperlegible as a body font because it’s been designed to be easy to read even at low resolutions or by people with low vision. It also works well for my ADHD brain — and I simply like how it looks.

I originally gave the background of the page an off-white color (which will be a light gray in the print version because that looks even better) because stark black-and-white contrasts are often uncomfortable to look at, especially on screens. At the same time, I made sure the contrast between text and background conformed to the AAA level (enhanced contrast) of the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) everywhere on the page. The blue-green color scheme also works well for colorblind people. The PDF is also tagged for easy screen reader navigation and contains image descriptions (alt-text).

I added a few swooshy lines to emphasize the different sections of the game, draw attention to important parts of the text, and create a less rigid overall appearance (again, to underline the improvisation theme).

I used the illustration to express the fun absurdity of the narratives that came out of all my playtests by turning an example starter scenario from the random roll table (“An octopus in a shopping mall wants to find a magic item but is hindered by tribbles.”) into an image. The illustration style also picks up the simple, quick, and fun vibe of the entire game.

In short: I wanted ImproVeto‘s visual design to be as approachable and accessible as its rules – and I hope you’ll find that I succeeded with both!

Conclusion

As you can see, even making a simple one-page game requires quite a few design decisions to make it into exactly what you want. I hope my efforts result in you having a lot of fun playing ImproVeto and realizing that the ideas you may have thought were boring are actually pretty cool (at least according to your fellow players), that it’s actually not that hard to invent or change things on the spot, and that vetoing things gets easier the more we do it.

If you have any questions or feedback about the game, please feel free to contact me on Mastodon (@this_curiouscat) or through the contact form on this website.

More information about ImproVeto / ImproVeto in our shop

This article was first published as part of the Tiny Tome Kickstarter campaign on June 07, 2022 and has been slightly edited for this version.

Neueste Beiträge

17. Juli 2024

Wir sind super stolz, dieses Jahr als Verlag für den internationalen Rollenspielpreis ENNIE Awards nominiert zu sein, in der Kategorie [...]

11. Juni 2024

Ich erhalte öfter mal Anfragen von Con-Veranstaltenden und interessierten Privatpersonen, ob Plotbunny Games dieses Jahr auf Rollenspiel-Con XYZ sei (oder [...]

18. März 2024

Florik hat gestern einen Blogbeitrag veröffentlicht, in dem er kritisiert hat, dass die Teilnahme an den Gratisrollenspieltagen für diejenigen, die [...]

14. März 2024

Auch dieses Jahr organisieren Cassandra und Manni von 3P - Partners in Pen & Paper eine Spendenaktion unter dem Titel [...]

4. März 2024

Es gibt auch dieses Jahr zu den Gratisrollenspieltagen ein neues Spiel von uns: Das Albtraumschiff! Nach dem durchschlagenden Erfolg von [...]

Weitere Beiträge

Wir sind super stolz, dieses Jahr als Verlag für den internationalen Rollenspielpreis ENNIE Awards nominiert zu sein, in der Kategorie Fan's Favorite Publisher. Die ENNIEs sind international vielleicht der wichtigste Rollenspiel-Publikumspreis, so dass allein die [...]

Ich erhalte öfter mal Anfragen von Con-Veranstaltenden und interessierten Privatpersonen, ob Plotbunny Games dieses Jahr auf Rollenspiel-Con XYZ sei (oder generell auf Vor-Ort-Cons). Daher dachte ich, ich schreibe meine Antwort auf diese Anfragen mal öffentlich [...]

Florik hat gestern einen Blogbeitrag veröffentlicht, in dem er kritisiert hat, dass die Teilnahme an den Gratisrollenspieltagen für diejenigen, die dort Material unter die Leute bringen wollen, Geld kostet und dass Kleinstverlage und Game Designer*innen [...]

Das Albtraumschiff, Dolly, wir haben ein Traumhaus gekauft, Follow, Fräulein Bernburgs Pensionat für junge Damen, Gegen das Monster, Hasi, wir haben einen Dungeon gekauft, ImproVeto, Magical Pets, Nagetiere mit Gitarren, Tipps zum Spielen, Unsere Spiele

Auch dieses Jahr organisieren Cassandra und Manni von 3P - Partners in Pen & Paper eine Spendenaktion unter dem Titel March 4 Kids. Dabei werden Spenden für das Ronald McDonald Haus in Lübeck gesammelt, in [...]